Triggered: Practical Exercises for Self-Regulation

by Andrew Florence

by Andrew Florence

Many of my working hours I am either actively team building, learning about team building, or even just thinking about team building–and I kind of loathe the phrase. Regularly, the practice is reduced to awkward icebreakers (aka icemakers) that whoever runs your meetings forces on everyone. You’ve probably been there. The meeting is just starting off, laden with awkward silence, and then the meeting facilitator strikes fear into your heart. He or she says, “We’re going to start off today with a little team building.” DUN DUN DUNNNNN!

There is a special level of dread that comes along with trudging through two truths and a lie, or attempting the oft-YouTube-Failed Trust Fall. In the virtual meeting context, this is when you start having those mysterious “technical issues.” The Internet goes out, or your cat sitting on your laptop, refusing to move for 15 minutes (or at least until those rocky icebreakers are done).

To make matters more complicated, team building has become a buzz phrase. People have thrown it around to the point of overuse, without any shared language and a major variation in practice. (Fortunately, team builders like Chris Cavert have come to some clarity around language, particularly with the difference between team bonding, team building and team development.)

Despite these challenges, team building is important, can create positive outcomes for teams, and has important implications for trauma-informed organizations. As a practitioner, I am fully committed to the power and connection created within teams, particularly during team building. In his book Community: The Structure of Belonging, Peter Block highlights the significance and power of small groups and teams, as they are the “structure in which employees and citizens become intimately connected with each other and in which the business becomes personal.”

What image best represents thriving to you?

Okay, but what on Earth do trauma-informed practices and team building even have in common? At Crossnore, we have commitments to this practice and regular connection opportunities across the agency.

A critical shift in our model is a focus that what happens at the organizational-level is as important as what happens at the micro-level. Our own norms, policies, and tools are as important as how we directly provide our services. By shifting our understanding that teams and organizations both experience and hold stress/trauma, we can see the significance of organization culture. In action, culture varies between organizations, but consists of “expectations, experiences, philosophy, as well as the values that guide member behavior, and is expressed in member self-image, inner workings, interactions with the outside world, and future expectations.”

A common organization development phrase states that culture eats strategy for breakfast—and one of the primary goals of team building is to nurture culture and move teams towards their conception of thriving. As teams experience stress, their culture can be a protective factor. Protective factors buffer team members from that stress and help them to be resilient. Google’s Project Aristotle suggests that one of the indicators of the most effective teams is high psychological safety. However, these things don’t just happen by accident—they take a lot of collaborative work! In team building, we are able to create novel experiential opportunities for team members. Here, they can engage with one another. They can work through problems and reflect on the group process. They can also apply successes to day-to-day challenges (and have fun along the way!).

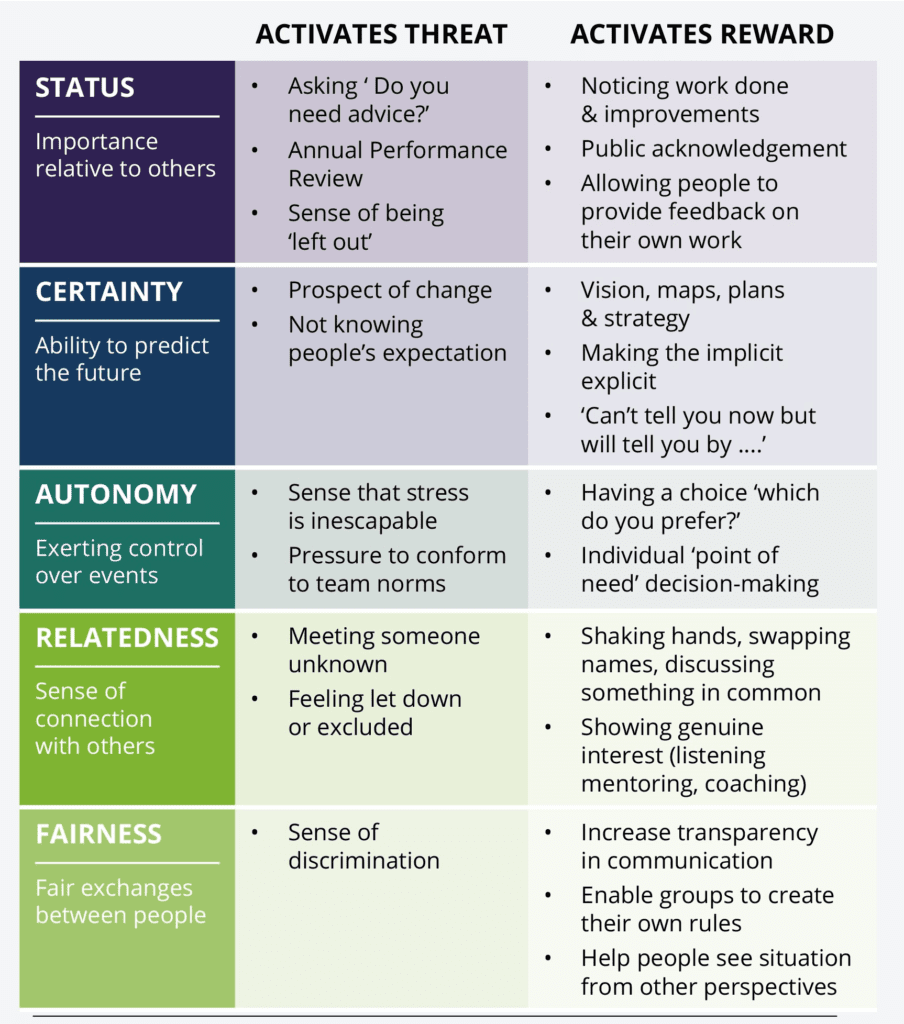

Team building is also a powerful practice in team care. One of the first things to go away in traumatized organizations are celebrations and recognition of what is going well. Team care is a regular way for team members to practice collective care, appreciations, and celebrations. During the inaugural Developing Leaders cohort at Crossnore in 2020, Brett Loftis shared with us the SCARF Model, developed by David Rock. This brain-based model identifies what is happening in our brains when we experience threats and rewards in the workplace. Within a team-building context, the SCARF model is one tool we can use. It helps draw attention to our fight/flight/freeze/appease response, and the ways our work is gratifying and meaningful.

How have you and your team utilized team building? What has changed by using those practices? What specific challenges does utilizing a team building approach sort out?

If you want to learn more about our approach to supporting teams moving towards thriving and building resilience through adventure, I would love to hear from you at aflorence@crossnore.org.