Triggered: Practical Exercises for Self-Regulation

by Andrew Florence

by Brett Loftis, JD

In the twenty five years that I have worked with young people, I have seen children in every imaginable state of stress and dysregulation. Fits of tears, yelling curse words, verbal threats to me and everyone in the vicinity, and even physical aggression. Often children can experience a different type of dysregulation and can appear completely shut down and borderline comatose. Early in my career, professionals would talk about children needing “anger management” classes and to learn “coping skills.” I even heard shaming language about “bad choices” made by “bad children.”

But in the years since the beginning of my career, we have all learned a lot about why children respond the way they do to stress and adversity. Now we understand the science of trauma and the impacts of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). When children have experienced early adversity, it impacts the structure and architecture of their developing brains. And even more incredibly, we now know that all of our brains experience neuroplasticity. Our brains have the ability to grow and heal as they encounter safety and new supportive experiences.

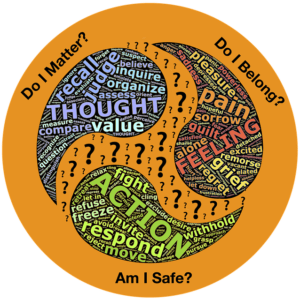

Research in brain science and neurobiology have given us incredible insight into our brains’ response to stress. It is now generally accepted science that when faced with high degrees of stress, our brains experience predictable responses of fight, flight, or freeze. This natural brain response, combined with the complicating impacts of previous trauma, requires that everyone in a position of helping or supporting young people be trained in these basic concepts of brain development and the impacts of adversity.

More importantly, all helpers need to understand how to recognize and respond to people and keep them safe when their brains get “highjacked” and stuck in a fight, flight, or freeze response. This transition takes time and specific training. It also takes a willingness to challenge what we think we know and how we have always done things. But refusing to make this shift can costs people their lives.

We have a recent heartbreaking example in Ma’Khia Bryant. Ma’Khia was a Black teenage girl killed by the police in front of her foster home in Ohio. According to news reports, Ma’Khia was at the home to celebrate a birthday. Because of an argument with her peers, she became fearful and called the police for support. While all the details remain unknown, there are some facts that my experience helps me to fill in. Ma’Khia was clearly experiencing a brain that was responding to a real or perceived threat with a fight response.

We know she felt threatened and unsafe because she called the police in the first place. We know that in addition to the stress of the situation, Ma’Khia had experienced previous trauma. Children in the foster care system have higher rates of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) than veterans returning from war.

Just the fact that Ma’Khia was in foster care tells us that she had experienced repeated episodes of adversity. That day, she was likely experiencing a trauma response to the events unfolding in that home. She was in her “survival brain” which means her brain was telling her she needed to fight to survive. Regardless of how her actions appeared to someone on the outside, it is important to think about what was going on inside her young brain. That insight is what saves lives.

We also know that police officers responding to the scene did not deescalate the situation. Their interactions with Ma’Khia resulted in her death. Many questions remain unanswered, but a few things are clear. The police intervention did not provide safety for Ma’Khia or the other young people. In fact, their presence and response escalated the situation. When a child who has experienced significant trauma is met with uniformed men using raised voices, yelling commands, and showing weapons, there is a predictable response.

The fact that Ma’Khia was a Black child raises another series of questions and deserves examination. Why did the responding officers perceive her as such a threat when she was the one that called them initially? What about their personal experiences and internalized biases led to their response with lethal violence? Some of the answers to these questions must connect to national data that highlights police as twice as likely to use force on black and brown people than they are on white people.

Additionally, it is well researched and documented that the ways we perceive the threat of harm and the ways we interpret threatening behavior is heavily influenced by internalized bias. Even clear bodycam footage does not tell the complete story. We must dig under the surface and face hard truths to prevent tragedies like this from happening again.

This tragic story and corresponding national data and research helps us to map out a different path forward. We now know better, so we must do better. Crossnore’s years of investment in trauma-informed care have taught us many things. This learning has changed the way we interact with children and adults. We know better, so we are doing better.

Also, we are not only concerned with changing the way individuals interact with people who have experienced trauma, but we are also mindful that organizational culture is equally important. We are one of a handful of organizations in the country to accomplish four separate rounds of national certification in our organizational model of trauma-informed care, Sanctuary©.

This deep organizational work led us to create the Center for Trauma Resilient Communities (CTRC) in 2018. CTRC has brought together the best trauma-informed care trainers in the country to help organizations and communities embed and embody the best science and trauma-informed care practices to build organizational and community resilience. This work is transforming how helpers and helping organizations do their work. Every person and agency that seeks to provide support and safety to vulnerable people must begin this process of education and implementation of trauma-informed care. We cannot afford to wait any longer. Our children deserve better.

Nationally, there are thousands of organizations transitioning to trauma-informed care. Some law enforcement agencies are also making important steps to change the way they do business, and trauma-informed policing represents an important shift in community policing. I can’t help but wonder if Ma’Khia Bryant would still be alive if the police had understood and implemented the principles of trauma-informed policing.

True trauma-informed care is also cognizant of systemic and structural racism. It builds knowledge and practices that create safety and address imbalances of power. To be trauma-informed is to pursue racial equity and justice. We are an agency that works directly with children in the foster care system. Daily, we see the intersection of trauma, racially disproportionate outcomes, and structures that fail children in families. Our commitment is to use best science and state of the art interventions to rewrite old scripts and provide hope and healing for the children who need us the most.